OCTOBER 2022

ASTAP – An excellent stacking program

Over the years, I have tried out several programs foraligning and stacking images and there is an article covering six of them inthe digest. I have usually fallen backto using Deep Sky Stacker (DSS) but have sometimes found that it was not ableto stack an image either as it could not find sufficient stars or that thestellar image quality was poor.

I have recently become aware of a free program, called ASTAP,which is often used for plate solving but also has the ability to align andstack frames. In a superb video from‘Nebula Photos’, its stacking performance was judged against seven others andwas rated second in image quality only to PixInsight – a quite expensiveprogram.

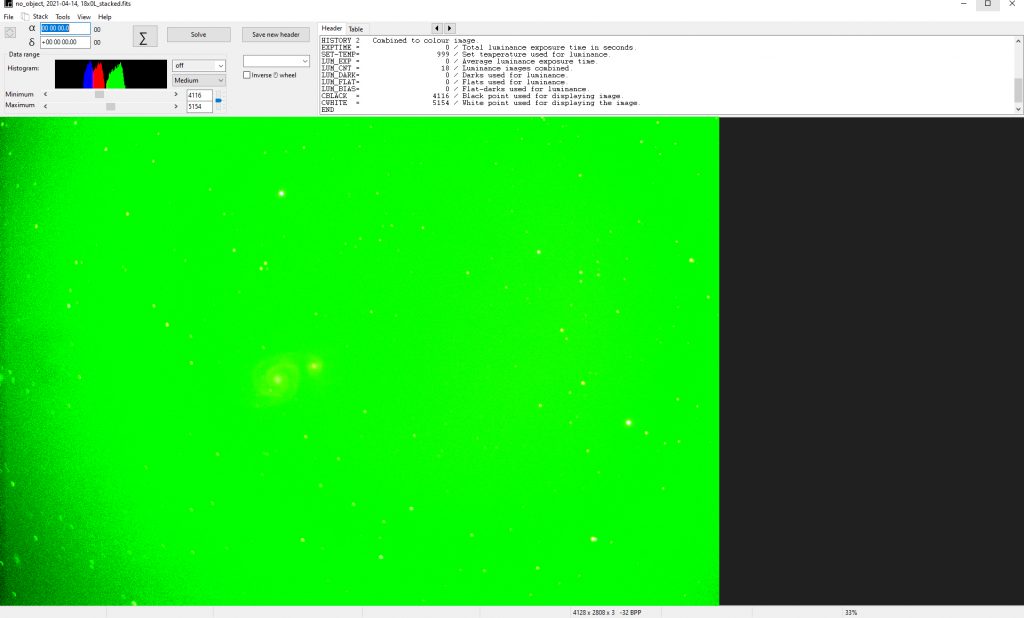

I thought that it would be worth trying out and submitted aset of 240, 20 second, images of Messier 51 which DSS had been unable to alignand stack. Very pleasingly, ATAP wasable to produce a good stacked image as seen below – the galaxy is justvisible.

When processed in Adobe Photshop, this gave the result shown below.

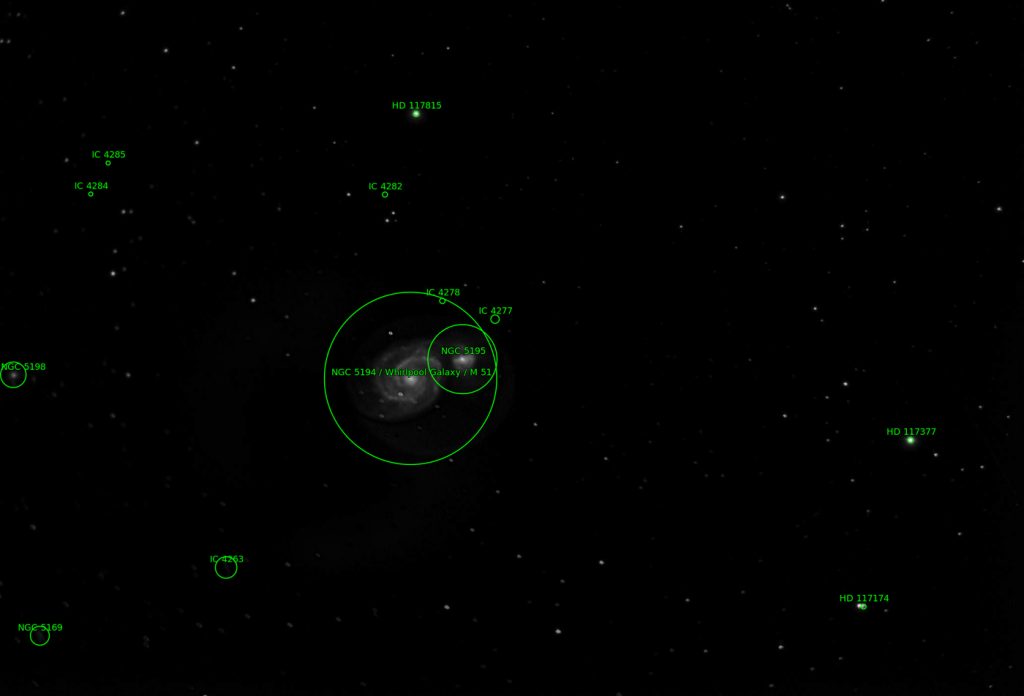

It is always useful to submit the image to Astrometry.net –which showed that the there were three other galaxies visible.

Alignment of the frames

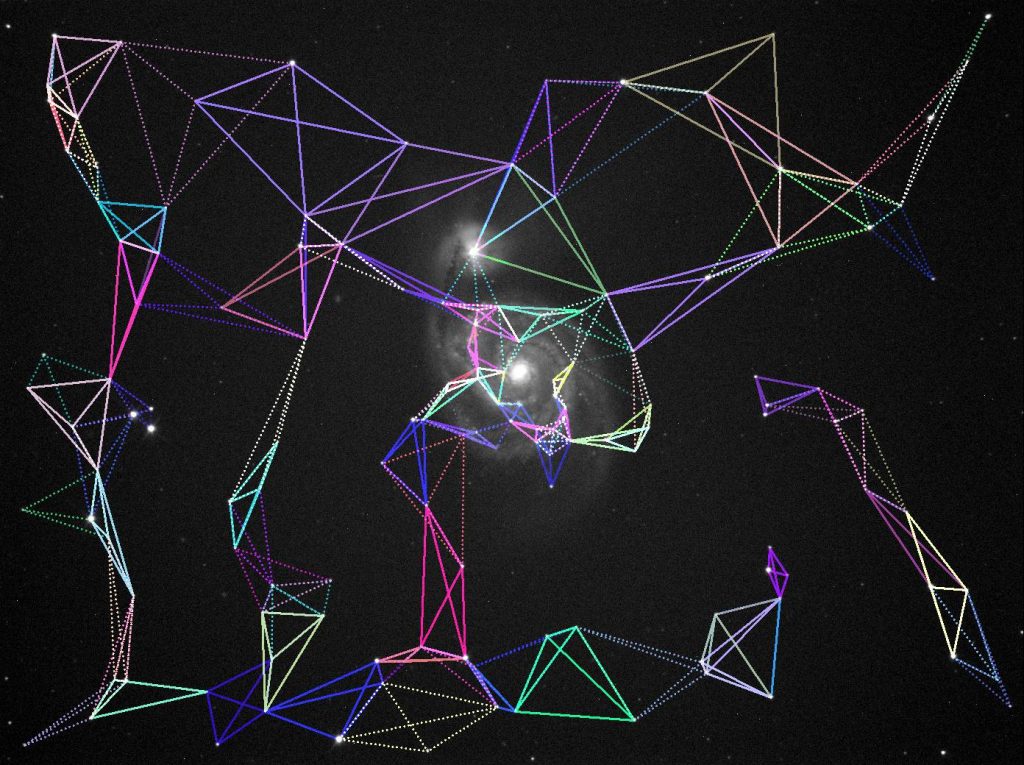

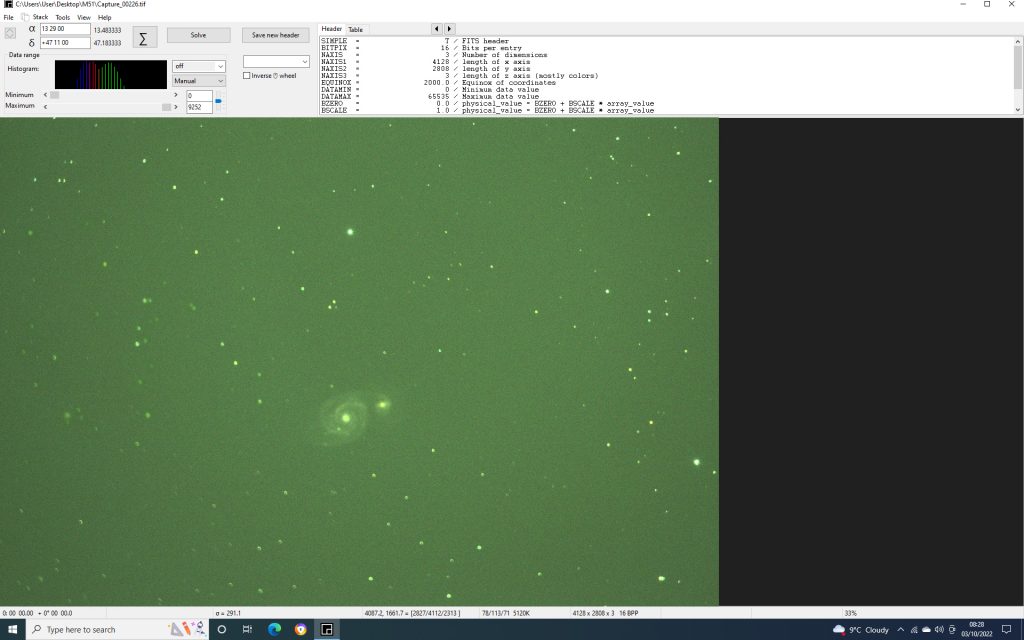

It does take significantly longer to align and stack the frames than DSS which I suspect is due to the way in which it aligns the frames. ASTAP uses a method similar to that used in plate solving. In each frame to be stacked, the program combines four close stars into an irregular 2D tetrahedron or kite like figure called a ‘quad’ as seen below – also in an image of M51.

It then matches these with the quads in the reference frame (when analysing the set of frames it decide upon the best and uses that as the reference frame). It selects at the best matches (perhaps up to 40) and ‘uses the centre position of the irregular tetrahedrons in a least square fitting routine to compute the offset and rotation of the specific frame to the reference frame‘. For each frame it produces two equations which determine how it should be shifted and, perhaps, rotated to align with the reference frame. As the stacking is in progress, one can see the number of quads used and the two equations.

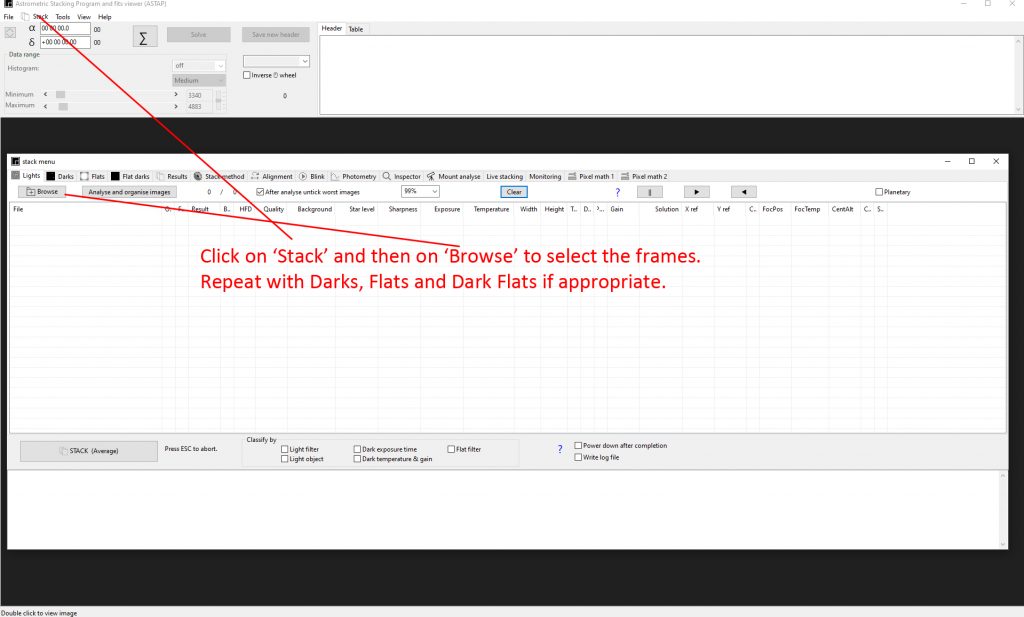

The aligning and stacking process

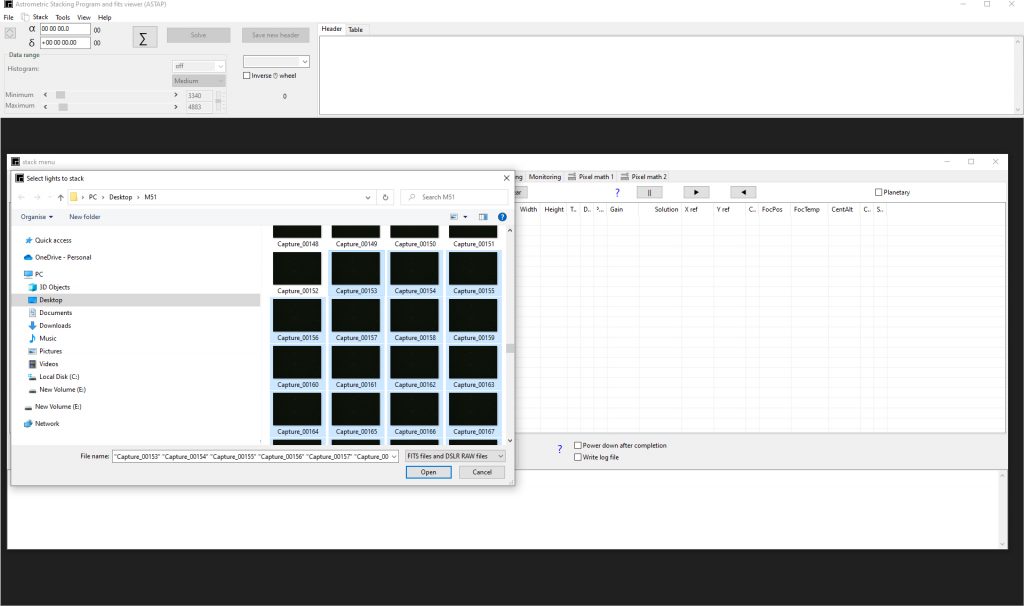

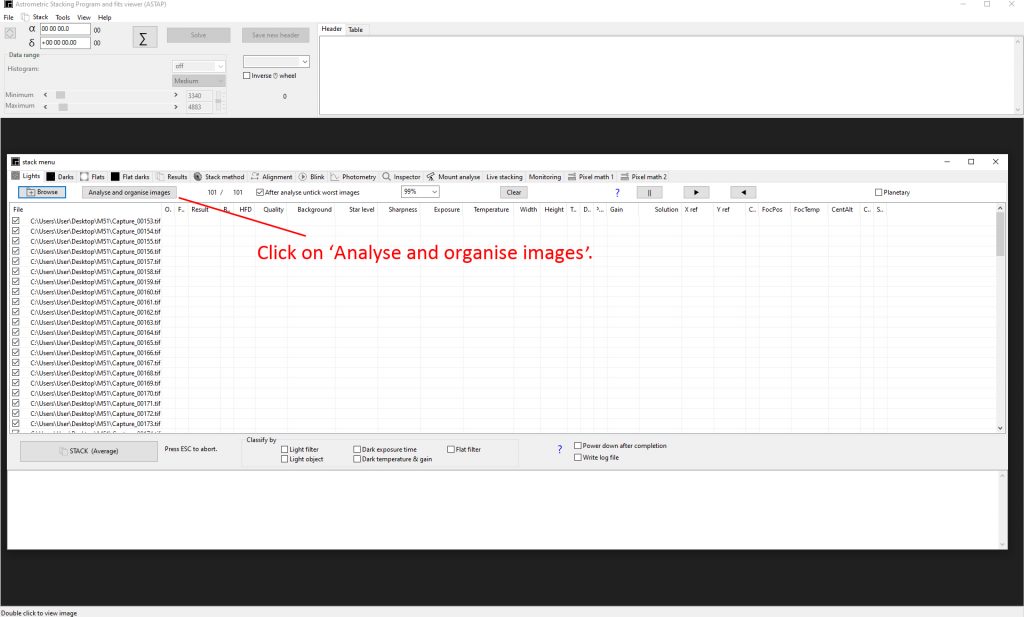

The light frames, along with the dark and flat frames if used, are imported into the program.

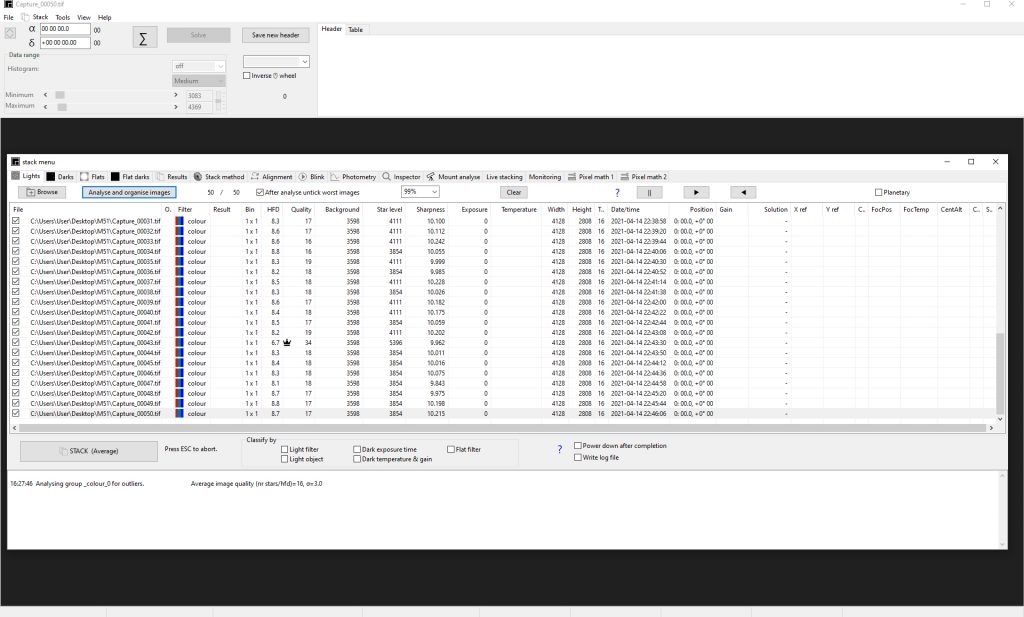

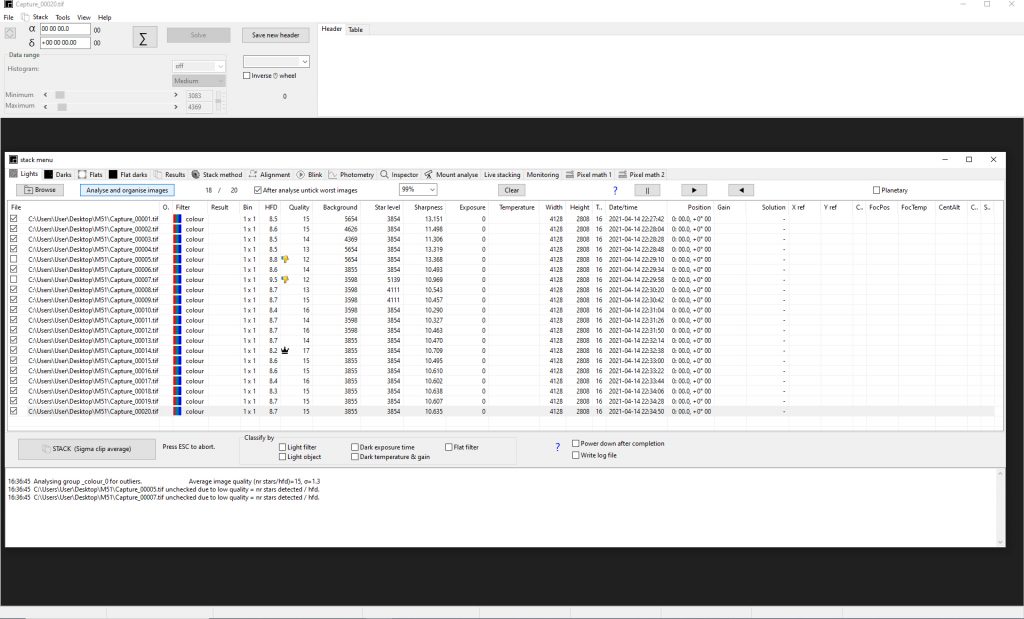

The ‘Analyse and organise images’ box is clicked and one sees the analysis data for each frame as it is produced. What is interesting is that, for each frame, it shows measures of star quality and also the relative brightness of the stars and air glow (light pollution).

In the case of the M51 frames, it was obvious that the light pollution was significantly less for the latter ~100 frames. The program will highlight with a crown the frame it regards as best and which it will use as the reference frame.

One will also see highlighted (thumbs down symbol) any frames that have been rejected due to poor star images – perhaps due to wind gusts that, for example, do affect some frames when I am using a 9.25 Schmidt-Cassegrain and large dew shield even when supported on a very sturdy mount.

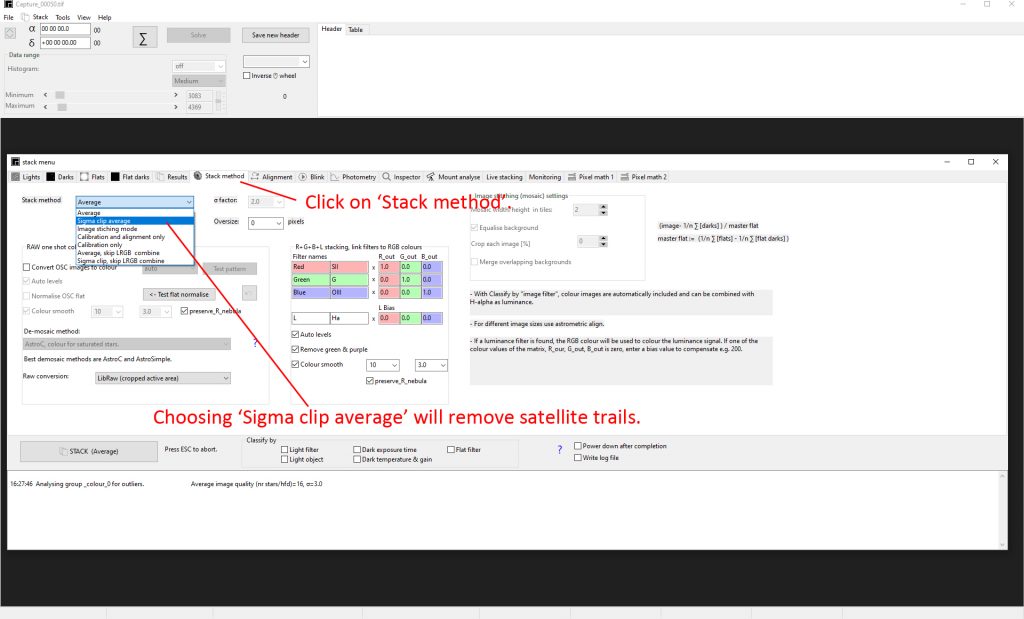

The simplest, as fastest’ stacking method is ‘Average’. However ASTAP recommend the ‘Sigma clipaverage’ which can be selected in the stacking modes menu. This will remove satellite trails providing areasonable number of frames are being stacked. In this case, there is a two pass stacking process. After the first pass, ASTAP computes theaverage value of each stacked pixel. Duringthe second pass, any pixel values which lie too far away from the average (thismay be by 2 standard deviations) arereplaced by the average value. This modewill increase the total processing time by about 50%.

The ‘Stack images ‘ is clicked upon and ASTAP works through the frames. Using an i7 Intel processor it was taking around 3 seconds per frame per pass (three passes if the ‘Sigma clip average’ stacking mode is used). In contrast, DSS takes around 1 second per frame when aligning and stacking with a further time required if the ‘Sigma Kappa’ stacking mode is employed. So ASTAP is slower by about a factor of 3. When complete, the result is automatically saved as a FITS file, but one can, as I do, then export it as a 16 bit Tiff file for further processing in a program such as Adobe Photoshop, the superb low cost alternative, Affinity Photo, or the new free program GLIMPSE. As is sometimes the case with other stacking programs, the image presented initially at the end of the process is stretched far too much and bears no comparison to that, shown above, when opened in the post processing program.

Adjustment of the histogram levels will give a more sensible image.

Stacking Test

I used ASTAP to process the data of Orion that I had used in the digest article comparing stacking programs. The result, shown below, showed excellent colour balance and saturation (perhaps the best) but did not remove the chromatic aberration around some of the brighter blue stars as had’ Images Plus’ and ‘Affinity Photo’. This is easy to correct and, on balance, I think it was one of the best in the test.

[Note: ASTAP did not like processing the Sony .arw raw files, so I first converted them into 16 bit Tiffs using the free program Raw Therapee.]

I think that the use of ASAP is pretty straightforward and feel that ASTAP will be now be my stacking program of choice for deep sky objects.